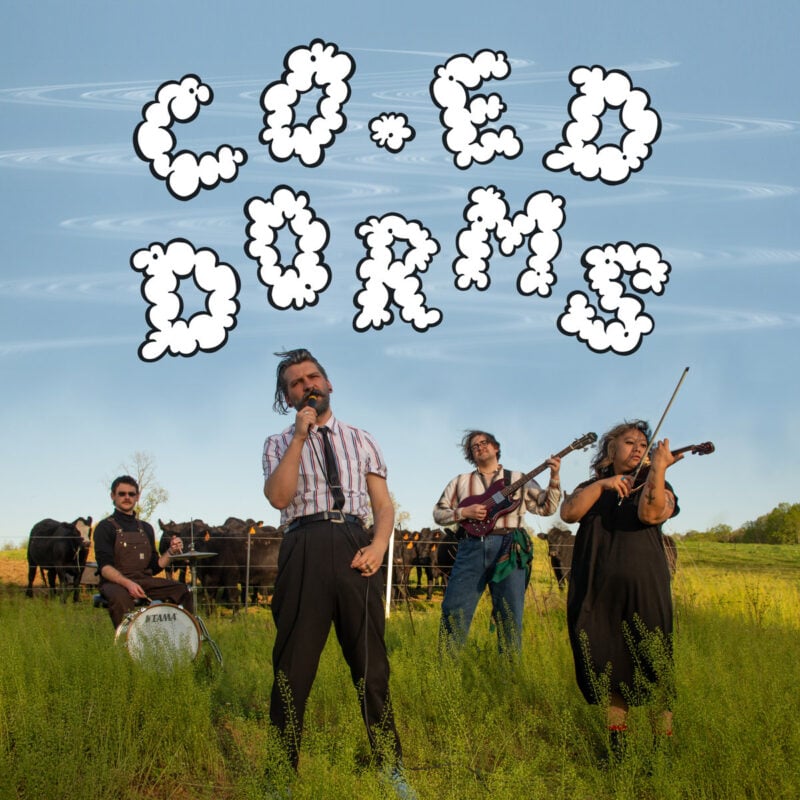

Experimental Post-Punk Outfit CO-ED DORMS Spin Murder, Money, and Modern Malaise Into Gothic Americana Poetry with Self-titled LP

CO-ED DORMS arrives like a small civic disturbance: four people dragging neo-classical intent through post-industrial grit, hammering post-punk revival energy into a performance-art crucible. Their arsenal is improbable but exacting: monologue-driven spoken-word tirades, a classically trained violin carving clean lines through the murk, a fuzz-bass that gnashes like a broken generator, and a live drummer routed through effects pedals until the kit behaves like a sentient, mildly panicked machine.

The effect lands in the uncanny middle ground between Cake’s sardonic smirk, Tuxedomoon’s downtown unease, King Missile’s absurdist brinksmanship, and Faith No More’s theatrical bite — with And Also the Trees’ pastoral drift, Neubauten’s cacophonous experimentation, and The Birthday Party’s feral swagger flickering through the mix. Spoken-word poetry slams against punk urgency and chamber-music poise. It’s a sound that shouldn’t balance, but insists on its own crooked equilibrium, muttering at the world with a clarity that feels both unhinged and overdue.

The record opens in a kind of cracked cathedral of modern chatter, where meaning drifts like paint fumes and The Pigeon staggers through its own cluttered agora, swatting at trend-choked voices and hollow declarations. With its thick basslines, rapidly bleating sax, and spoken-word vocal snarl, it feels like a dispatch from a campus where no one listens yet everyone performs, where creation is confused with credentials, and where the real struggle is simply to hear oneself think. COED-DORMS frame that din, not as a low-grade spiritual emergency, but an appeal to wake from the narcotic glow of the feed and remember that art is a human act, not a marketing trick.

Feeling Good (Oh, Yeah) continues the band’s avant swagger, strolling in like a man swinging his arms under a forgiving sun, delighted for once that the world hasn’t found him yet. A buoyant, rubber-band bassline underpins the strut, keeping everything light on its feet even as the tension coils. Then the refrain erupts with dramatic, rapid string stabs — a breathless volley that cuts straight through the mix, prodding the vocal hook upward with manic insistence. But even here, in this borrowed brightness, the shadow mutters its reminders. The track knows that joy is weather: fleeting, movable, a temporary lease on a body that remembers storm systems too well. There’s a melancholy baked into the grin, a readiness for the inevitable downturn, and the cheap grace of enjoying the moment anyway.

Violins zig-zag a ackadaisical lament about Money that gives way to a snarl, dragging the listener back into the fluorescent cruelty of labor. Here, work is a cosmic joke played on the underpaid, the exhausted, and the terminally online. The song, replete with a dramatic violin solo, hammers at the absurdity of performing pride in a job that devours identity, mocking the myth that choosing drudgery is somehow noble. It’s a litany of neighbors decaying under lawn care and liquour, a meditation on a society so broke it laughs just to kill the silence.

Breaking from the present entirely, The Horseman’s Tail has a western feel to its rhythms, sound, and melody, while a southern vocal drawl sinks into a dust-choked parable of a killer collapsing under his own history. Led by a powerful violin, the song plays like an American Gothic tale told by lantern light. No salvation waits in scripture or medicine; only the slow rot of consequence. He stumbles through the land as if reenacting every cautionary tale ever muttered on a porch at dusk, one more tough man felled by a world that never gave him softness.

There’s a cadence to Strut’s delivery that feels part Birthday Party, Part “Apples and Oranges” Pink Floyd, but with the former’s Western twang. Though ultimately sounding like a towncryer in Tombstone, the song drags us back to the modern digital grindstone, spitting bile at the culture of shortcuts and recycled gestures. It’s a manifesto written on a smudged napkin at closing time: stop pandering, stop mimicking, stop mistaking technical polish for vision. The band lashes out in defense of the sacred belief that art must bruise a little to matter. It’s an exhortation to walk one’s own crooked path rather than chase algorithms.

The album tilts again into the hypnotic dread of The Wall, where dark spoken-word bile is spewed over jazzy industrial experimentation — where a simple surface becomes an oracle of memory, absence, and encroaching heat. The song, or perhaps the poem, transforms a blank expanse into a treacherous companion, one that embraces until the embrace becomes unbearable. It is the quiet horror of being alone too long with something that cannot speak back.

The album’s short interlude, QUIET DOWN, hammers down its request for peace and quiet, offering a grim little comedy of the aging ear, a neighbour mourning the empire of silence he believes he once ruled. Beneath his scolding lies loneliness, the sick ache of realizing that joy has moved next door and won’t shut up.

Next, Milk Drinker settles into a slower, more contemplative sway — post-punk bass gently pulsing beneath a soft mesh of strings, the whole thing moving with a restraint that feels almost resigned. The somber detachment doesn’t explode outward so much as unfold inward, like someone muttering through an existential crisis they can barely admit they’re having. Absurdity, privilege, and wounded pride still shape the lyric’s strange monologue, spiraling from mock-philosophy into dairy-soaked grievance, but the delivery feels quieter, more bruised than bombastic. The song skewers entitlement not by shouting it down, but by revealing how insecurity slips on the mask of authority when no one is looking. It becomes a subtle, darkly funny hymn to the ways people rationalize their comforts even as the world around them cracks — a smirk delivered under the breath instead of through a bullhorn.

Murder on Main Street arrives with a ’60s beat-poet groove and a crime-narrator’s hush, the rhythm shuffling forward like a gumshoe keeping his collar high against the rain. The strings stab in slow, Hitchcockian pulses — a Psycho motif dragged through Southern grit — giving the track that unmistakable Bad Seeds tension without tipping fully into pastiche. It’s less murder ballad than murder manifesto, delivered with a weary conviction that suggests the story has been lived, not invented.

As the song unfolds, its noir veneer begins to fray. What starts as a rain-soaked investigation — footprints, suspicion, breath fogging in a streetlamp’s glow — gradually dissolves into something quieter and far more devastating: a confession of economic despair. The narrator isn’t hunting a killer; he’s explaining why he created one. Cornered by circumstance, boxed in by a world that’s grown too tight around him, he stages his own disappearance in a last, impossible bid to secure a future for the person he loves.

In its final breaths, the album suggests that the true American tragedies aren’t crimes at all, but the desperate choices people make when the world leaves no room to breathe.

Listen to CO-ED DORMS below and order the album here.

Follow CO-ED DORMS:

- Spotify

- Bandcamp

The post Experimental Post-Punk Outfit CO-ED DORMS Spin Murder, Money, and Modern Malaise Into Gothic Americana Poetry with Self-titled LP appeared first on Post-Punk.com.